Background

A black box is “a system where only the inputs and outputs are observable, while the internal workings are unknown or incomprehensible”. Examples surround us in everyday life: smartphones, car engines, the human brain, and same game parlays.

A Same Game Parlay (SGP) is a sports bet where you combine multiple selections (legs) from the same game into one parlay. For the parlay to win, all selections must hit.

The catch with SGPs is that since the legs are all in the same game, sports books take the correlation between the bets into account, adding a de facto correlation tax to the payout. This tax varies depending on the sportsbook and the individual legs in a given SGP. It’s calculated from running complex sports models, making it difficult to analyze for the common sports bettor.

In this article, I am going to explore the house edge of same game parlays, diving into its implications for profitable sports betting and attempting to answer the question: Is the correlation tax on SGPs too much?

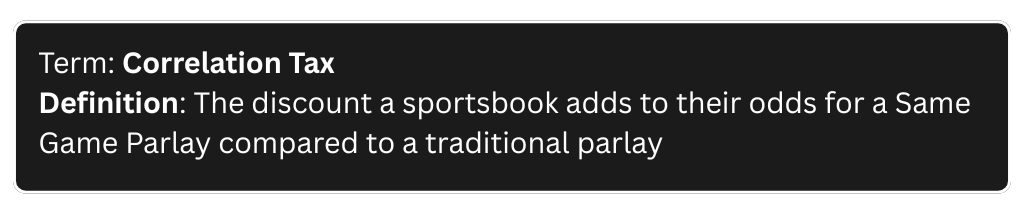

The Correlation Tax

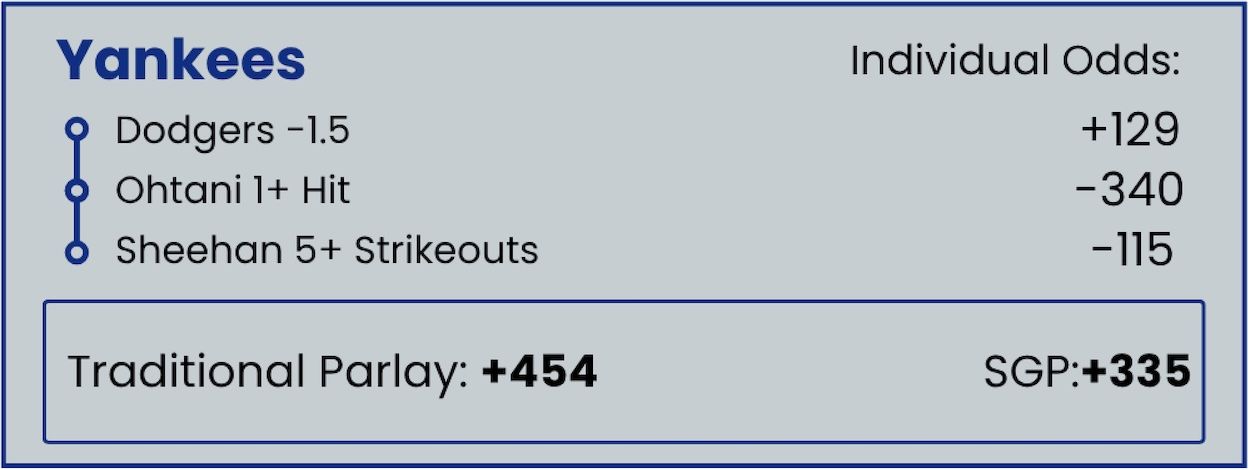

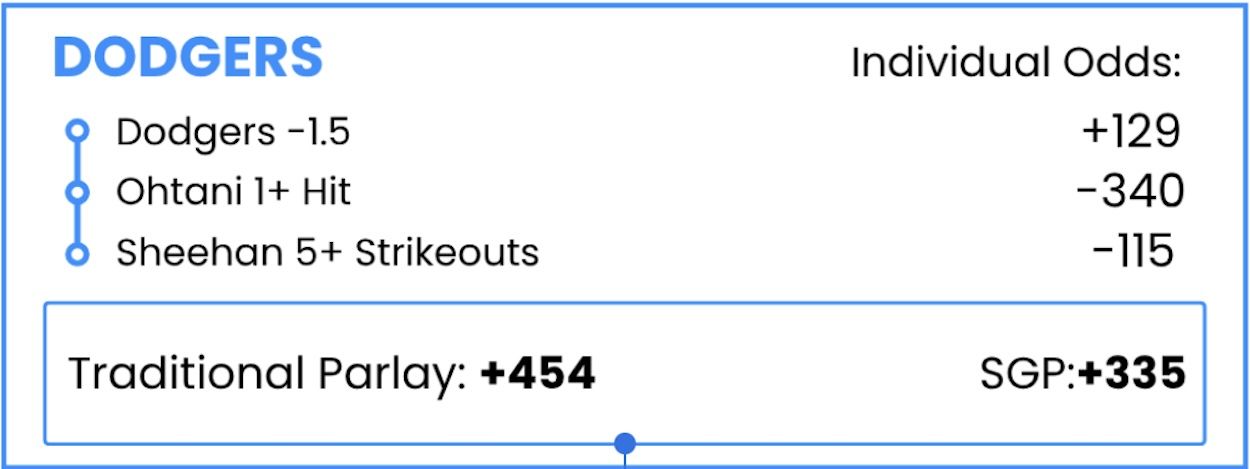

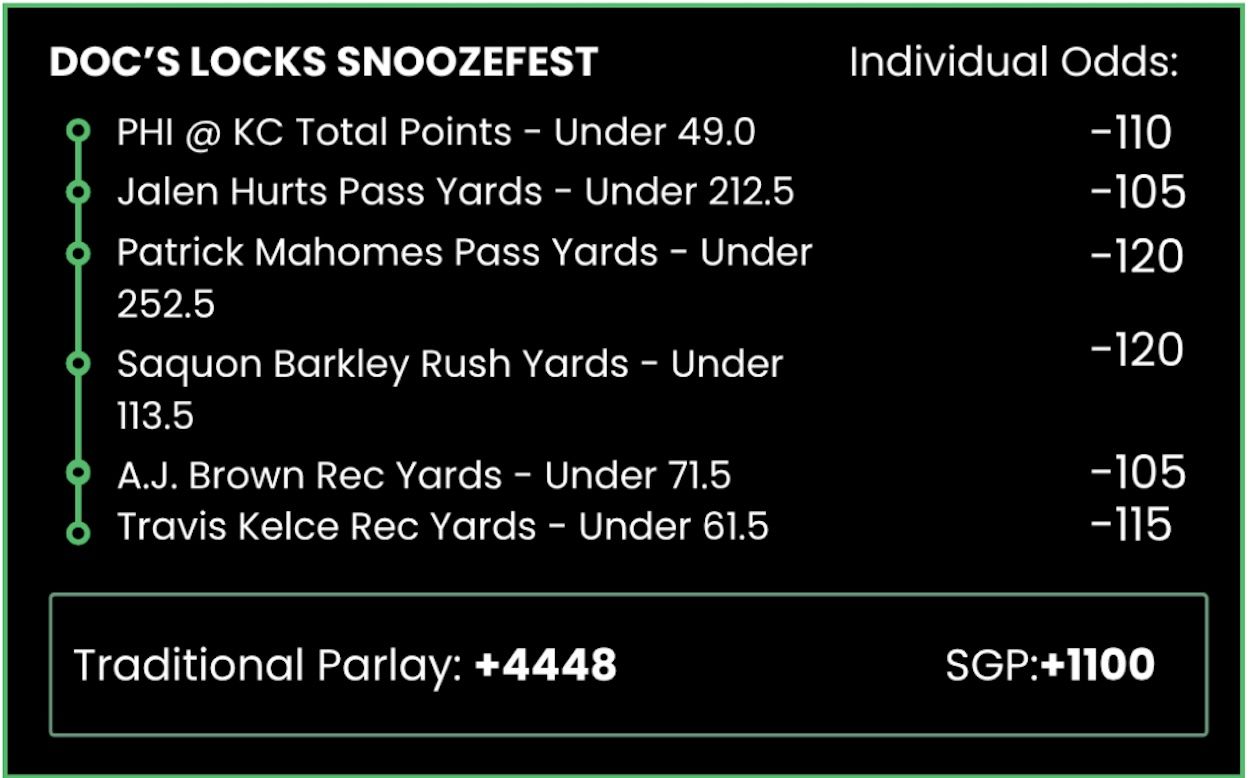

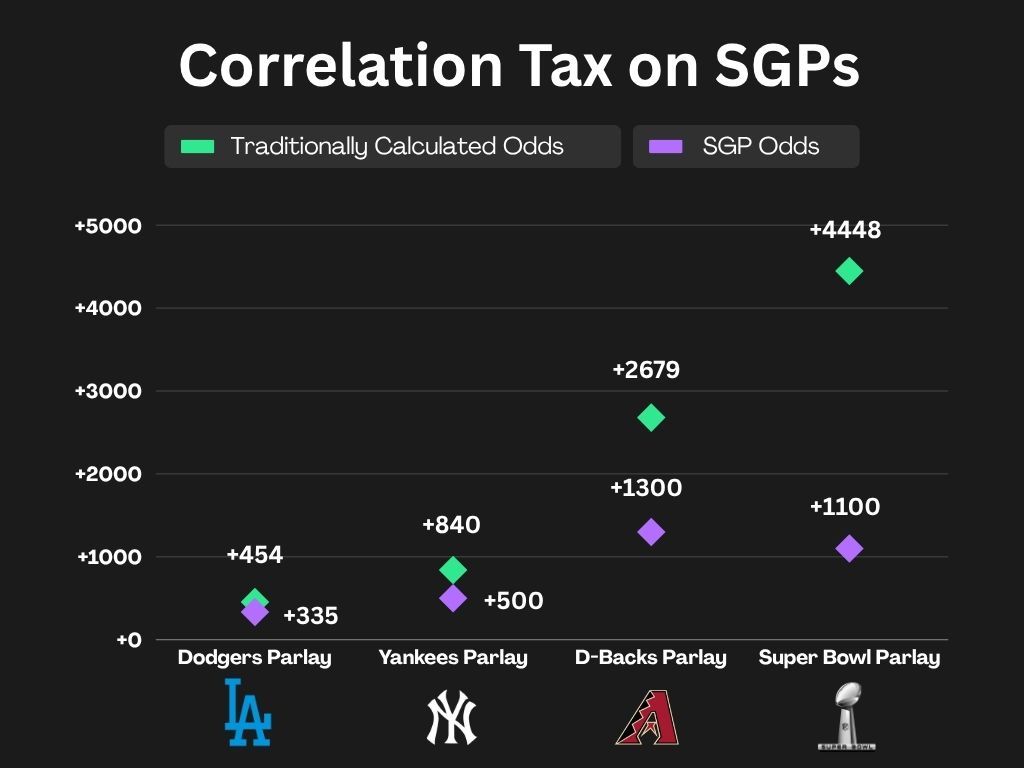

To visualize the added correlation tax of SGPs in practice, we’ll examine three recent MLB parlays and WagerWire’s Doc’s Locks Snoozefest from Super Bowl LIX.

Each slip displays the odds of the individual legs of each bet, the odds if they were calculated as a traditional parlay, and the odds when priced by the sports book as an SGP.

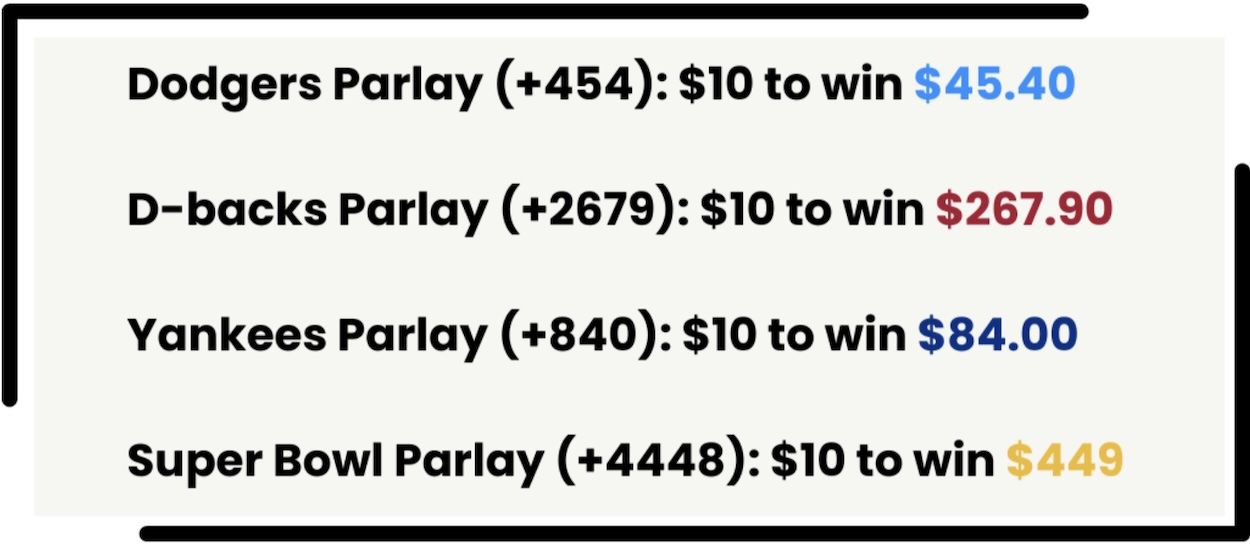

If these were traditional parlays and a $10 bet was placed on each one, the bettor would be offered the following odds and payout:

As an SGP, the correlation-adjusted profits:

As you can see, the house tacks on a significant correlation tax on the payouts of SGPs.

Now, we should not expect SGPs to be priced the same as traditional parlays since there is a correlation factor at play. But, the varying correlation tax the sportsbook applies creates an added variable bettors need to account for.

It’s difficult to determine if this tax is too much on a bet-by-bet basis, as this requires meticulous modeling of each individual parlay. But, when examining the publicly available and profitable history of SGPs for the sportsbook—not to mention their ubiquitousness in sportsbook marketing, a red flag in itself—it becomes apparent that on the whole bettors are getting swindled.

The -30% ROI% Trap

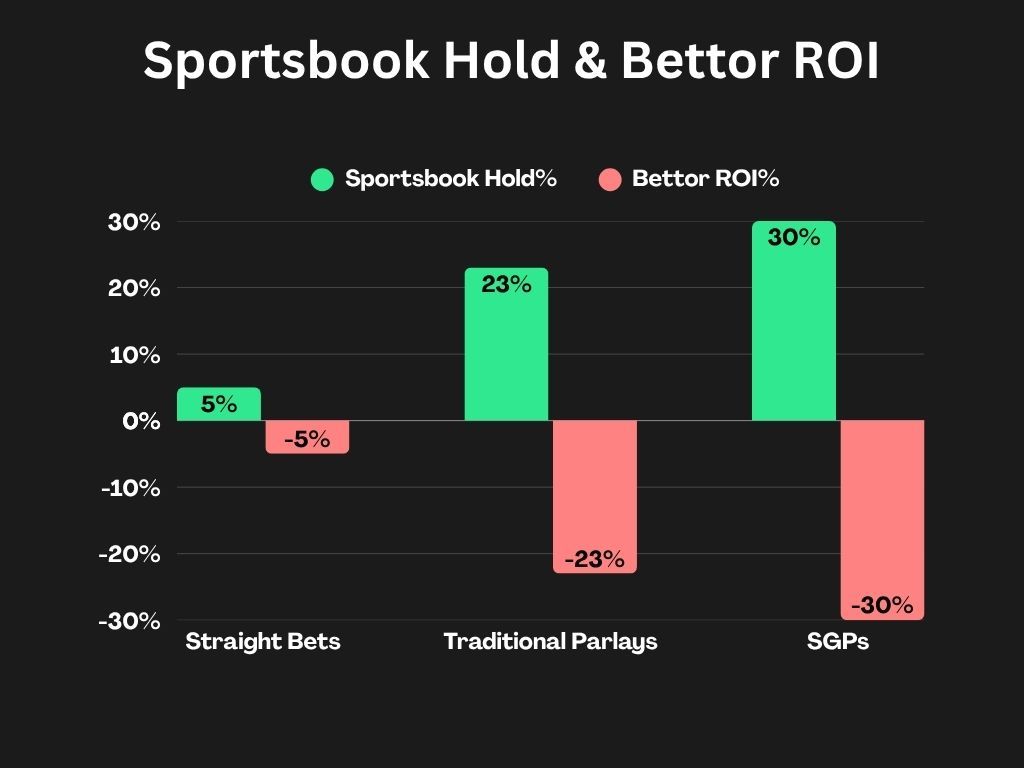

The hold of a sportsbook is “the percentage of money that sportsbooks keep for every dollar wagered.” It's one of the most-used metrics for gauging a sportsbook's profitability. Each type of bet (straight bets, futures, parlays, etc.) carries a different structural hold, with some bet types favoring the sportsbook more than others.

Definition: “Hold” (and how it compares to “Vig”)

A 2022 study from the UNLV Center for Gaming Research found that Nevada sportsbooks produced a hold percentage of around 30% for same game parlays. Single game, straight bets were around 4-5% and traditional parlays fell somewhere around 23%. This makes SGPs one of the most profitable products for sports books, a clear sign that many bettors have tried—and failed—to beat them.

One way to directly contextualize how sportsbook hold percentages affect bettors is to show how they relate to a bettor’s return on investment percentage (ROI%). The relationship between the two is actually quite trivial: the negative of a sportsbook’s hold percentage is equal to a bettor’s ROI%. Thus, using the SGP hold percentage from the study, SGP bettors have carried a horrendous ROI of negative-30%. On the other hand, for straight bets, their ROI% has been around negative-5%; still a net loss, but not nearly as steep.

This significant difference in ROI% demonstrates that on the whole the SGP correlation tax is clearly excessive (and a fast track to going bust if bettors aren’t practicing sound bankroll management). To explore and visualize this overpenalization further, we can actually use the negative-30% ROI% figure to estimate the exact amount of vig attached to our SGP examples from earlier.

Translating SGP Hold% to Vig

Judging the fairness of the correlation tax of an individual SGP is a daunting data science task, requiring the calculation of the true probability of the SGP. However, by using the hold percentage of SGPs from the study we can generate a reasonable estimate of the true probability of a SGP given the sportsbook’s offered odds.

Specifically, using the bettor’s ROI of negative-30%, we can do some algebra to work from the sportsbook’s offered odds to the fair odds.

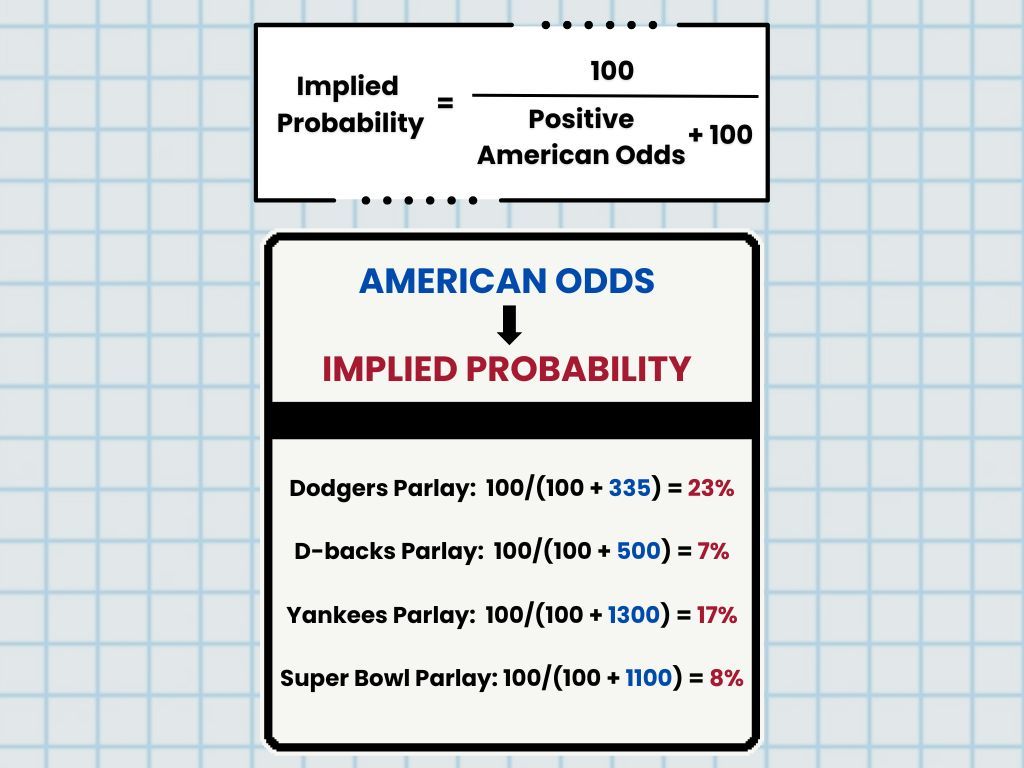

Circling back to the examples from the beginning of the article, we can now use this strategy to estimate their true probabilities and fair odds. To start, we convert the offered American Odds from earlier into their implied probabilities.

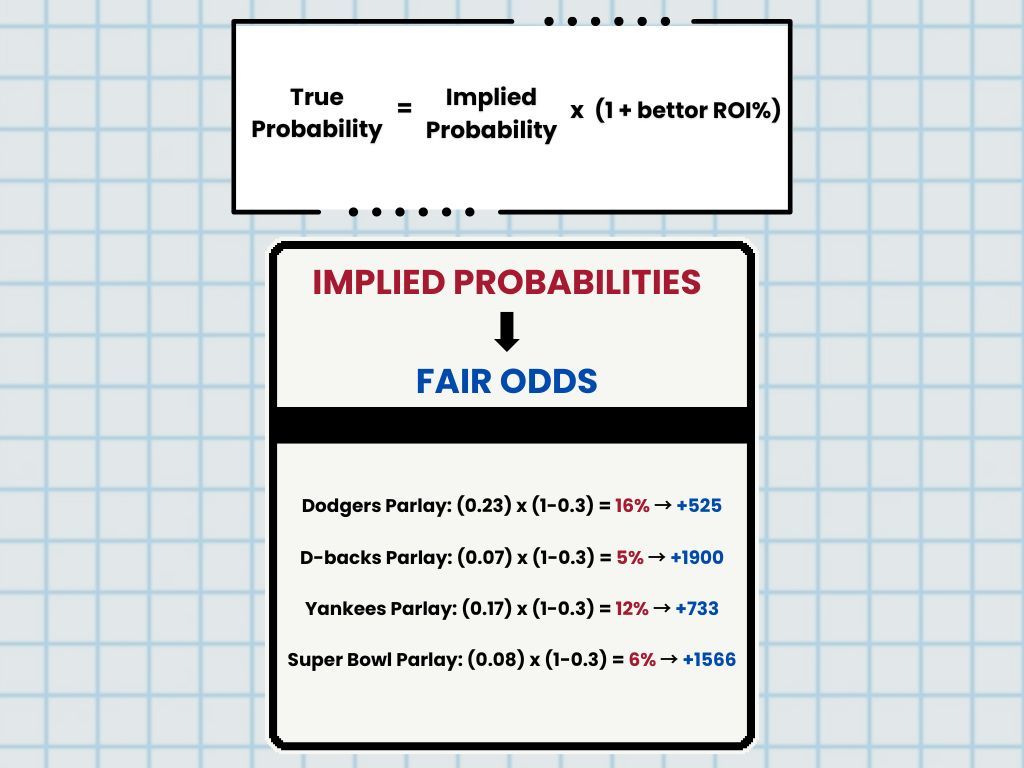

Then, we use the following formula to estimate the true probability of the SGP, and at the end convert back to American Odds:

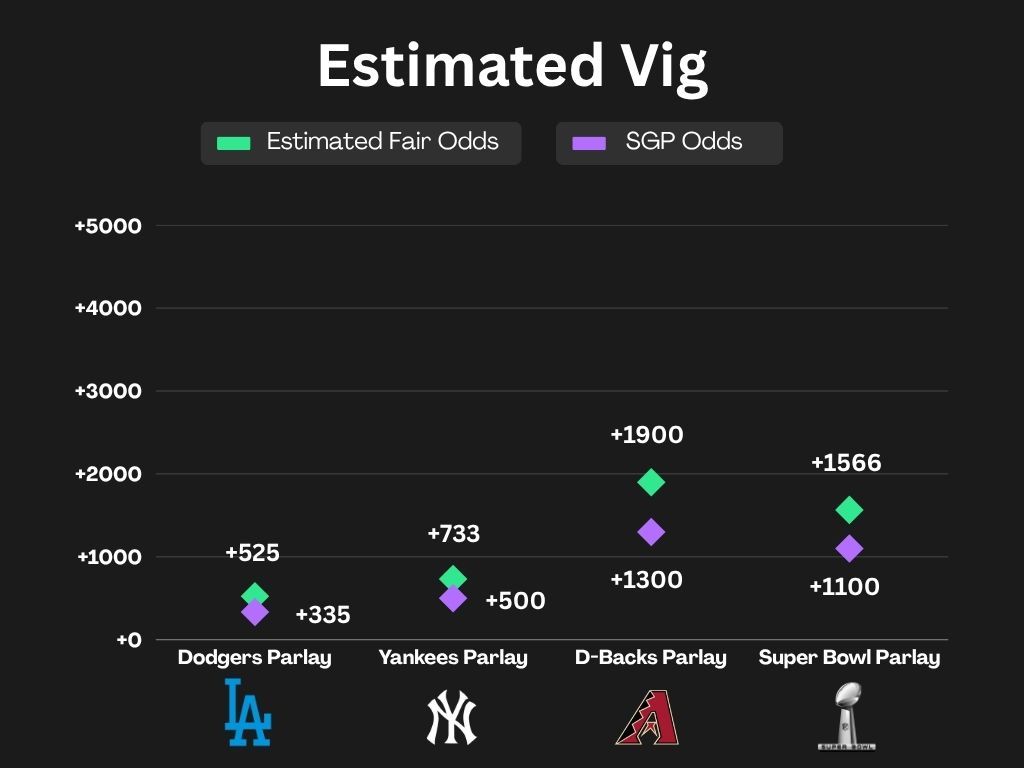

Now that we have an estimate of the true probabilities of the SGPs, we can see exactly how much extra vig the sportsbooks are adding to these SGPs with their correlation tax by comparing their offered odds to what the fair odds should be.

As the graph illustrates, the difference between the offered odds for each of these SGPs and their estimated fair odds is significant, with each bet reflecting the study results and carrying an expected ROI% of negative-30% for bettors.

Now, we should not expect there to be zero vig, as the sportsbooks add a vig to every bet in order to make a profit. Additionally, it's possible our estimate of the true probability is inaccurate for any one of these SGP bets, as they could hold a profitable angle with a large edge. But on a macro scale, SGPs carry a larger vig than any other bet types as evidenced by their disproportionately large hold percentage.

Conclusion

While SGPs are appealing for their entertainment value, it’s best to avoid them if you’re looking to be profitable long-term.

The difficulty of accounting for correlation, coupled with the disproportionately high hold percentage taken by the house, means bettors must be confident they have a significant edge on a given SGP.

For casual and recreational bettors, your money is better served targeting lower-hold markets with a more reasonable vig.